Excel 2004: ‘You cannot enter more than 100 Characters’

Posted by Pierre Igot in: MicrosoftJuly 26th, 2007 • 10:41 am

Yet another Microsoft-sponsored WTF moment… I mean, here I am, having to do a translation of an English document that is a table in an Excel file. It’s mostly text, but it’s a table, so I guess Excel was deemed an appropriate tool for authoring this particular document. I don’t know—I am just the translator.

So I am typing away in Excel table cells, constantly cursing Microsoft engineers for having invented these two incompatible editing modes where common keyboard shortcuts involving the cursor keys have different behaviours depending on which mode you are in—and of course there are no consistent visual clues regarding the mode you are currently in. But anyway, that’s another story…

Most of the cells contain a few lines of text, so on top of it all I have to deal with the ugliness of Excel trying to cope with vertical alignment issues… Not a pretty sight.

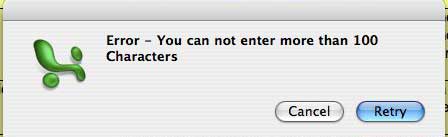

And then all of a sudden, I type a few lines of text and I press Return to go to the next cell, and I get this:

Can you believe this? I have absolutely no idea where this comes from. I am not aware of anyone ever having imposed restrictions on the number of characters you can enter in table cell. And even if it were possible, I am entirely sure that the author of the document that I am translating has not imposed any such restrictions anywhere in his document.

Of course, the error message is not even true. If I hit “Retry” and try again, I get the same error message. If I hit “Cancel,” Excel erases the entire contents of the cell. But if I type the same text elsewhere, then cut and paste it into the same cell, Excel doesn’t make a peep, and the text is indeed there in full, non-truncated, over-100-chars glory.

Microsoft’s products are really the only Mac software that is so crappy that it still unexpectedly, randomly comes up with such absurd error messages which seem to result from weird computer code time warps. I mean, I suppose there might have been a time, circa 1983, where it was indeed impossible to enter more than 100 characters in an Excel table cell. This error message must have come from somewhere.

But that it would surface now, in 2007, while I am editing a table in Excel 2004 under Mac OS X 10.4, in a document and an application which obviously do not suffer from such restrictions, is simply beyond belief.

And it’s so bad that the single-sentence message is not even written properly. Check out the capital “C” on “Characters” and the missing period at the end. It’s mind-boggling.

I really do believe that this particular error message must be in a piece of code that is left over from the 1980s. There is no other possible explanation.

As for identifying the actual behaviour that is causing this particular bug/message to surface, don’t even get me started… Microsoft also specializes in bugs that are impossible to reproduce reliably, so that they don’t even have to fix them.

Yet, you know, I didn’t invent this dialog box. It really did appear on my machine this very morning, i.e. on July 26, 2007 at 10:30 am AST.

As I said—it’s unbelievable.

July 26th, 2007 at Jul 26, 07 | 12:13 pm

Uh, ‘can not’, classy!

“Yet, you know, I didn’t invent this dialog box. It really did appear on my machine this very morning, i.e. on July 26, 2007 at 10:30 am AST.”

It’s really strange but sometimes when filing bug reports I am also tempted to add that, no, I’m not making this up, I didn’t even deliberately try to play games on the software, I just tried to use it…

July 26th, 2007 at Jul 26, 07 | 2:48 pm

Does that file have Data Validation turned on? (Select the cell that was giving you problems, then go to the Data menu and select Validation.)

That error string doesn’t appear anywhere in the source code that I can find, but may possibly be a custom error message defined in a data validation criteria.

July 26th, 2007 at Jul 26, 07 | 3:57 pm

Schwieb: You are right. I guess there are cells in this table that do have Data Validation enabled, and it does specify that the text length must be “less than 101.” So I guess that’s where the error message comes from.

I cannot imagine, however, why these cells would have this feature enabled. It’s just a few cells in a table that otherwise does not have any such restrictions, and the affected cells are perfectly identical to the other ones in all other respects. I guess I would have to try and communicate with the author of the document to find out—although I suspect he wouldn’t have a clue either.

And the third tab of the Data Validation dialog does indeed contain the text of the alert message, complete with the capital C and the missing period. So it looks like it is not a Microsoft-blessed error message :).

I can only imagine that this person accidentally reused an existing spreadsheet that had such restrictions in place for some cells, not realizing that these restrictions were there, because of course there is nothing in the visual appearance of the cell that indicates the presence of such restrictions

So basically my original post is too harsh on Microsoft. But the fact remains that these things happen because of the way Microsoft software is designed. Too many options, not enough visual clues, too much power in the hands of users without enough training. These things only happen in Microsoft software.

And let’s not forget that, in spite of the supposed data validation, Excel is perfectly willing to let me paste text that is 200 or 500 characters long in those very cells… The data validation only applies when the cell is in “cell editing” mode. But you can paste stuff without switching to that mode.

July 26th, 2007 at Jul 26, 07 | 4:19 pm

I agree that being able to paste into a cell with Dval is indeed a bug. I am glad to find out that the original problem is indeed due to specific workbook settings and not to an underlying defect (temporarily sidestepping any referendum on the design of Dval or how your client may have turned it on unknowingly.)

July 26th, 2007 at Jul 26, 07 | 7:04 pm

OK, I’ll bite. Consider this scenario:

1. Large, corporate customer calls their MS rep. “We’ll buy (or upgrade) Excel licenses, but you gotta add a data validation feature tool.

2. Some MS manager looks at the numbers and determines, yes, this customer is important enough so the request must be satisfied. (Or, enough requests like this from enough large customers have been received.)

3. Someone at MS Marketing writes a list of minimum specifications for what will satisfy the customer(s), possibly actually even checking it with them.

4. The specifications are handed over to Engineering, and the question is asked, “Can you add this without breaking Excel?”

5. The answer is returned, “Sure, as long as we aren’t held responsible for really consistent application data checking, that is, we can just sneak it into the ‘cell editing’ software, which is pretty much modular. Mind you, data pasted into cells won’t be checked.”

6. Marketing person says, “Yes, that’s fine, go ahead, but spend as little money and take as few chances as possible.”

7. Engineering gives the assignment to a software engineer two years out of college…. and, eventually, he/she gets it done and it is added to the product… and the feature list.

8. But by this time, the customer (s) requesting the feature have moved on to some different way of solving the problem. Still, everyone is happy, they’ve done their job, the features list –the central criteria of most corporate managers– has grown, and most of all, MS has made more money.

—-

As we’ve been discussing now –it seems, ad infinitum– too many features added to MS Office products look like they’ve been added through a process like this one. The new features don’t integrate harmoniously; they are often restricted to what one can do without disturbing the main mass of spaghetti code that almost certainly still comprises the main machinery of these programs. The implementation looks like it’s one-to-one with a specific customer demand, rather than a thoughtful extension of functionality.

How Dilbertesque!

———

I’ve never heard of Excel “Data Validation”. If I had noticed it on the menu –I see it now– I might have taken a look and decided I had no use whatsoever for it. My quick impression is that, yes, it would certainly suffice for many simple situations for relatively unsophisticated users … but it probably isn’t appropriate to give spreadsheets to those users anyway, and –in practice– I’d guess Data Validation isn’t used very much. And most of the people who try to use it find it is pretty inflexible.

Kind of like toaster-oven option for an SUV, I guess…

—–

The most telling aspect of this incident is that Pierre couldn’t tell what he was up against because the error message was left entirely up to the user, the original author who may have actually had a good reason for adding a limitation of 100 characters. (Maybe 5 or 10 years back, many versions of the spreadsheet ago!) Or not — it might have been a really silly reason, or just someone experimenting with the Data Validation tool.

Providing consistent context is clearly an expensive proposition…

Pierre, you are asking, over and over again, to be empowered. But you are using products designed to limit user knowledge and choices, implemented by people with lots of reasons to do avoid doing more than the minimum on the check-off list.

July 27th, 2007 at Jul 27, 07 | 12:34 am

How much easier this would have been if the error message identified itself as a data validation error — i.e., if it had a Microsoft-designated title and a user-definable area within the message, rather than being left entirely in the hands of the user.

July 27th, 2007 at Jul 27, 07 | 9:39 am

I agree that one of the core issues here is that the data validation warning looks exactly like a regular, built-in Excel dialog. There is no visual indication that this is a user-defined dialog. I suppose that, in theory, it is good that Excel “developers” who want to design spreadsheets with specific features can add them in a way that makes them look like they are part of the Excel application itself—but in practice it fools even users like me into thinking that these dialogs are part of the application and, of course, they can reflect badly on the application itself.